On March 26, 2021, the Second Circuit reversed a 2019 district court ruling and held that Andy Warhol’s “Prince Series” did not qualify as fair use of Lynn Goldsmith’s 1981 photograph of Prince (the Photograph). The Court further concluded that the Prince Series works are substantially similar to the Goldsmith Photograph as a matter of law.

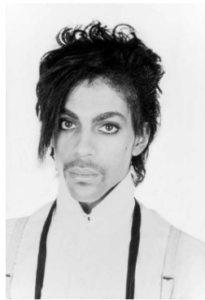

At issue in this case is a series of prints created by Andy Warhol based on Lynn Goldsmith’s Photograph, below, in which she holds a registered copyright.

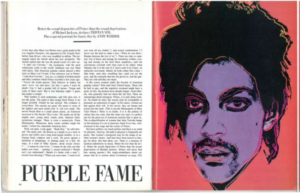

In 1984, Goldsmith licensed the Photograph to Vanity Fair, which then commissioned Warhol to make an artwork based on it. Warhol’s illustration, together with an attribution to Goldsmith, was published with an article about Prince and appeared as follows:

Warhol went on to create 15 more works as part of the Prince Series. The Prince Series comprises of fourteen silkscreen prints (twelve on canvas, two on paper) and two pencil illustrations, and includes the following images:

Goldsmith claimed that she was not aware of the Prince Series until 2016, when Prince died, and Condé Nast published the Prince Series without any credit to her. Soon thereafter, she notified The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. (AWF), successor to Warhol’s copyright in the Prince Series, of the perceived violation of her copyright in the Photograph.

In 2017, AWF preemptively sued Goldsmith for a declaratory judgment that the Prince Series works were non-infringing or, in the alternative, that they made fair use of the Photograph. Goldsmith counterclaimed for infringement. The district court granted summary judgment to AWF on its assertion of fair use and dismissed Goldsmith’s counterclaim with prejudice. Goldsmith appealed, arguing that the Prince Series artworks were not a transformative use of her image. The Second Circuit agreed and reasoned that “[t]he Prince Series works are substantially similar to the Goldsmith Photograph as a matter of law.”

In the opinion penned by the Hon. Gerard E. Lynch, the Court analyzed the four factors of the fair-use defense to copyright infringement pursuant to 17 U.S.C. § 107, which are: (1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. The Court held that each of these factors favored Goldsmith.

The main question in the Court’s analysis was whether the district court correctly considered the first factor. One aspect of that factor is “transformative use,” which means adding something new or altering the copyrighted work with new expression, meaning, or message. Traditionally, criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, research, or parody have qualified as transformative use. The Court disagreed with the district court’s holding that the Prince Series works are transformative because they “can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure.” The Court explained that “whether a work is transformative cannot turn merely on the stated or perceived intent of the artist or the meaning or impression that a critic – or for that matter, a judge – draws from the work.” The Court also cautioned judges from assuming the “role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue … because judges are typically unsuited to make aesthetic judgments and because such perceptions are inherently subjective.”

Instead, the Court explained that “the judge must examine whether the secondary work’s use of its source material is in service of a ‘fundamentally different and new’ artistic purpose and character, such that the secondary work stands apart from the ‘raw material’ used to create it.” The Court further clarified that it means that “the secondary work’s transformative purpose and character must, at a bare minimum, comprise something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work such that the secondary remains both recognizably deriving from, and retaining the essential elements of, its source material.”

Based on the foregoing, the Court concluded that the Prince Series is not “transformative.” The Court further reasoned that, despite Warhol’s modifications, the Photograph remains the recognizable foundation upon which the Prince Series is built. The Court also noted that it is entirely irrelevant that “each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol,’” and explained that “[e]ntertaining that logic would inevitably create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege; the more established the artist and the more distinct that artist’s style, the greater leeway that artist would have to pilfer the creative labors of others.”

With respect to the “commercial use” aspect of the first factor, while the Court recognized that “AWF’s mission is to advance the visual arts,” it also noted that, nonetheless, “Warhol and AWF are [not] entitled to monetize it without paying Goldsmith the ‘customary price’ for the rights to her work.” Thus, the Court concluded that the first factor favors Goldsmith.

The Court also held that the remaining three factors favor Goldsmith.

- The second factor considers the nature of the copyrighted work. The Court reasoned that the fact that Goldsmith made the Photograph “available for a single use on limited terms does not change its status as an unpublished work nor diminish the law’s protection of her choice of ‘when to make a work public and whether to withhold a work to shore up demand.’”

- The third factor considers “the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole.” The Court explained that the copyright protection as applied to photographs encompasses the photographer’s artistic choices, including posing the subjects, lighting, angle, etc., which manifest in the image produced. The Court reasoned that Warhol used the Photograph itself and significantly borrowed from it so that the Prince Series works “are instantly recognizable as depictions or images of the Photograph itself.”

- With respect to the last factor, the Court reasoned that although the primary market for the Photograph and the Prince Series may differ, the Prince Series works pose cognizable harm to Goldsmith’s market to license the Photograph to publications for editorial purposes and to other artists to create derivative works based on the Photograph and similar works.

As a result, the Court held that AWF’s defense of fair use fails as a matter of law

The Court further concluded that the Prince Series works are substantially similar to the Photograph as a matter of law. The Court noted that AWF has conceded that the Photograph served as the “raw material” for the Prince Series works, and Warhol produced the Prince Series works “by copying the Photograph itself.” Thus, the Court concluded that “given the degree to which Goldsmith’s work remains recognizable within Warhol’s, there can be no reasonable debate that the works are substantially similar.”

Both Judge Sullivan and Judge Jacobs joined in the opinion of the Court, and wrote separate concurring opinions.. Judge Sullivan, joined by Judge Jacobs, highlighted the overreliance on “transformative use” in fair use jurisprudence, generally, and suggested that a renewed focus on the fourth fair use factor, “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work,” 17 U.S.C. § 107(4), would bring greater coherence and predictability to this area of the law.

Judge Jacobs wrote to point out that the holding does not consider, let alone decide, whether the infringement encumbers the original Prince Series works that are in the hands of collectors or museums.

This opinion represents a steep retreat from the high water mark of transformative use dominating the fair use analysis, including the Second Circuit’s own Cariou v. Prince, 714 F.3d 694, 706 (2d Cir. 2013).